Classic Content: When Johnny Edwards Came Home

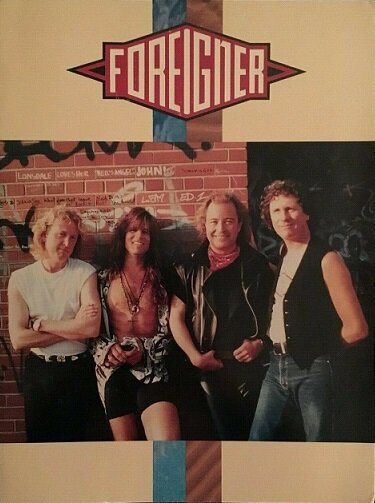

Johnny Edwards performing with Foreigner in 1991.

Twenty years ago, I met a local music legend at Twice Told Coffee Shop in the Highlands. It was a humid summer evening — July, 2001, to be as precise as possible — and I recall that we sat outside for our interview. I had recently seen his reunited band Buster Brown open for Detroit’s the Romantics in a Waterfront concert. Johnny, of course, had a stint touring and recording as the lead singer for Foreigner. My story, written for Louisville News, was about him surviving the music business and getting back to his roots. (Note: In the years since, I have been contacted numerous times by people hoping I still had Johnny's contact info. I don’t, sorry.)

***

August 2001

Johnny Edwards seemed as excited to be TALKING about being on stage as he seemed June 8 when he WAS on stage. Sitting one sunny evening at Twice Told Coffeehouse in the Highlands, his home territory, Edwards' eyes sparkled as he talked of one of the thousands of gigs he's played in a music career that began more than three decades ago.

But this wasn't the croaking of a wanna-be rocker or a crusty has-been who longs to be 25 again. Instead, it was more of a thoughtful recollection of how he came to be where he is at this moment in time, like a collection of photographs displayed chronologically in an album that tells a distinctive story that isn't finished yet.

No, the story isn't quite finished. Not yet.

Edwards, you might remember, made his mark in Louisville back in the early 1980s with a band called Buster Brown. But he went a lot farther than that, and only a couple years ago came back home to settle where he always felt most at home in the first place.

How did a Louisville boy who'd been in a regional band called Buster Brown get onto the radar of an established national act like Foreigner?

You might not know that he spent some time with a hair metal band called King Kobra that scored a few hits in the late 1980s and that for a couple of years he was the front man for Foreigner, the arena-rock band that seemed bigger than life for many of us in middle school and high school. Pretty big stuff, especially for a Kentucky boy.

And yet here he was, sitting in a tiny coffeehouse in Louisville, wearing a T-shirt and gym shorts, a backpack close by his side. This is a guy whose trade, these days, is in telecommunications. He's got a wife, kids, a house. Lives just around the corner from his parents in the house where he grew up. These days, he's much more dad and a husband than rock star.

If his honesty didn't shine through his sincere eyes and his easy mannerisms, you'd almost have a hard time believing the story he was telling.

From Buster Brown To L.A.

Steve Holmes actually founded Buster Brown in 1970. Johnny Edwards, who was the lead singer for the band during its heyday, didn't come along until a few years later. But as bands are wont to do, personnel came and went, the group got tighter, and Buster Brown grew into something of a regional hit.

While Buster Brown never made it nationally, its remaining core certainly did well for itself. A producer named Steve Klaussman - who founded Tesla and discovered Ronnie Montrose - had seen Buster Brown, and he coaxed Edwards and drummer James Kottak to Los Angeles. They would make an album called Mean in 1987, backing Montrose, and while that album didn't exactly top the charts, it would eventually lead to big things. Kottak would go on to drum for Kingdom Come and Warrant, he is now the regular drummer for a German metal band you might have heard of: the Scorpions.

"Johnny and James were in a band called Buster Brown," Montrose said in a 1997 interview with reporter John Wardlaw, "and I really enjoyed working with them. Had I known that Buster Brown wouldn't have stayed together I'd have suggested we go out and tour a little bit with that band. But at that point I was under the assumption I was just borrowing John and James from Buster Brown and they were going to go out and do that, so I just enjoyed it. A bunch of silly rock songs, but I enjoyed it."

A band called Northrup was the next step for Edwards, which included bassist Larry Hart and guitarist Jeff Northrup. That band toiled in anonymity and put together a decent catalog of original tunes but couldn't manage to get a recording contract.

"Jeff had a lot of songs," Edwards said. "We just never could get a deal." Finally, the group gave up.

"It was sort of at the end of the power rock thing," Edwards said. "At the end of Northrup, we were desperate for something - anything. Carmine Appice offered to pay us to come in and be his band."

That's the Carmine Appice who was the front man for the aforementioned King Kobra. By that time, however, the Kobra had mostly run its course, as heavy metal was overstocked with the likes of Bon Jovi and Whitesnake. But Appice was pushing hard to reinvent King Kobra. So an album was made and many gigs were played. "We did it for kicks, really," Edwards said. "It did basically what we thought it would do: pretty much nothing."

But Edwards' wild ride was only beginning.

Arena Rock Comes Calling

Johnny Edwards didn't find Foreigner. Foreigner found Johnny Edwards.

Lou Gramm, who had been the lead singer and one of the creative forces of Foreigner since the band's inception, had decided to move on to a solo career. Foreigner wanted to tour, because most of the band, since they were not receiving big songwriting residuals like Gramm, weren't making money unless they were on the road.

"They said, 'Let's put an album together, and Lou can decide if he wants to come back," Edwards said. "Lou said no, and they found me."

The question: How did a Louisville boy who'd been in a regional band called Buster Brown get onto the radar of an established national act like Foreigner?

"I had tapes floating around," Edwards said. "I had quite a few people at Atlantic Records who liked the tapes. Ironically, I had just signed a contract with Atlanta for another project, Wild Horses," a band that leaned toward high-energy roots rock, much like Buster Brown.

"It was around the time the Black Crowes were coming on; kind of an English blues sound," he said.

But Mick Jones of Foreigner was insistent on Edwards joining the band who had brought "Hot Blooded," "Waiting on a Girl Like You" and "I Want to Know What Love Is" to the annals of pop history.

Jones flew to Los Angeles on a private plane owned by Rolling Stone magazine and invited Edwards to his hotel for breakfast. "He started blowing all this smoke up my ass," Edwards said. "Then I met with the band and the management, and they really turned up the heat."

Yes, Jones managed to talk Edwards into flying on the Rolling Stone express to New York, where he did an audition. There was another singer in the running, but the band met with him and the chemistry wasn't there.

"My wife wanted me to do it," Edwards said. "They made me a huge offer."

So Johnny Edwards replaced Lou Gramm, who, to many fans from the late 1970s and early '80s, WAS foreigner. Just like that. And he enjoyed it.

"It was great, man," Edwards said, shaking his head as if still in disbelief that it actually happened. "We wrote 12 songs and recorded them over a period of six or eight months between New York and England. We did a promotional tour and met all kinds of people in all these great places. It was a thrill."

But there was always an element of doubt in Edwards' mind. To him, that doubt was merely the call of reality. It was 1990. Foreigner was decidedly a band of the early '80s. He knew that going in and was OK with it. But he soon realized he was, within the band at least, alone in his thinking.

"They really thought they could put this album out and sell a ton of records," Edwards said. "When I found them, I thought they were already done for. It took me a while to figure (their thinking) out. I just said, 'Well, I guess this is just the way my career is going to turn.'"

Cover of Foreigner press kit circa 1991, with Edwards, second from left.

The album, titled Unusual Heat, came together, and the band grew more excited. Again, that feeling wasn't universal.

"The tunes sounded real generic and plodding," Edwards said. "Our manager knew it too. It was a huge concern, because Mick was living in a fantasy world."

As it turns out, Edwards' fears were well-founded. The album entered the charts in the 170s and hung there for several weeks.

"I remember having this big meeting, and they were like, 'What are we going to do?'"

The album would eventually sell about 400,000 albums in the United States, which is shy of being a gold album. Not bad, but it certainly wasn't the numbers Jones and Foreigner expected. The tour wasn't much better. It consisted mostly of being booked in huge venues - which, on concert night, were about half filled.

"We always got a good response at the gigs," Edwards said. "Even the press was pretty decent. Rolling Stone even had good things to say - but Mick had Rolling Stone in his back pocket."

Nevertheless, he said there was "ridiculous pressure" on him in general in the role of replacing Lou Gramm. It was not unlike Journey replacing Steve Perry (which it has done) or Judas Priest replacing Rob Halford (which it has done) or Van Halen replacing David Lee Roth, which ... well let's not get started on that.

But the pressure was really more physical than social. All of Foreigner's songs, he said, were in such a high pitch that singing them night after night wore on his vocal chords - even though he had a durable voice from years of fronting bands.

"I did my darnedest, but the songs were always way up high," he said. "They did that on purpose in the studio to get the most out of the songs, but when you do that night after night, it's almost impossible."

Mercifully, the tour ended, and Foreigner returned to Los Angeles to start writing songs for the next album and tour. Edwards worked with Jones on 10 or so songs, but they never became finished products. Meanwhile, comfortable in his new role, Edwards began the process of buying a house in L.A. In the meantime, he and Jones continued to meet regularly to work on the new songs.

The house deal finally closed, and Edwards and his family moved in over a weekend. He had told Jones he was moving and wouldn't be able to work for a few days. But more than a few days went by and there was no contact. Edwards, having plenty to do, didn't fret. At least, not for a while.

"About a week later Mick called and said, 'You know what? I'm sorry, but Lou has decided to come back with the band,'" Edwards said. And that was that.

Apparently they had been negotiating with Gramm for quite a while. Gramm's project, called Shadow King, hadn't exactly taken the world by storm either.

That band was signed to Atlantic as well, and, as one would expect, the label had grown weary of paying both bands for unsuccessful products. So, Lou Gramm returned to Foreigner (although the band's fortunes didn't improve much), and Johnny Edwards found himself living in a house he couldn't afford on the backside of a recording contract. He was, at this point, another out-of-work musician in L.A.

Easy Come, Easy Go

Edwards' wife went to work to help pay the mortgage. Johnny Edwards, meanwhile, went right back to finding his way in the music business. He got together with a few other musicians he'd met along the way and formed a band called Royal Jelly. On the strength of some strong 8-track demos, the band got a recording contract with Island Records almost immediately.

The band went back into the studio to re-record the songs, and the group's self-titled debut album was born, with help from producer Matt Wallace. It was met with almost universal indifference, for a variety of reasons.

For one, Edwards said, "the label didn't know what to do with it." The album was very much alt-pop, with a funk flavor. Also, his bandmates were, like him, ex-members of bands of varying degrees of success, forcing it to deal with a lot of "formerly of" baggage. Edwards, of course, had Foreigner and King Kobra on his resume; drummer Jeff Klaven had pounded the skins for Krokus. Heck, even Susannah Hoffs of the Bangles played tambourine on that album, even though she wasn't really a member of the band.

"They actually marketed us that way, and it was hard to get a foothold," Edwards said. It was, unfortunately, 1995, and a time when new rock was what sold. Despite the disappointing reception, however, Edwards to this day has no regrets.

"It was the best thing I ever did musically," he said. "That's the only thing I've ever done that I can listen to today without throwing up. I always said if I could record one album I was proud of, I would be satisfied."

Royal Jelly was the one. When it failed, Edwards knew it was time to move on.

"I walked away from it without any regrets," he said. "We could have continued on, but by that time I had two little girls and it wasn't fair to my wife at all."

So in late 1995, Johnny Edwards went back to work 9-to-5 for the first time in years. Four years later, he made the decision to move back to Louisville, arranging to buy the Highlands home his parents had owned for years. His mother and father, both of whom, now in their 80s, are very active in the Fellowship of Reconciliation here in Louisville, now live in a house just around the corner.

Coming Around

Edwards just smiles when he's asked why now, why Buster Brown again. Hooking up with Kevin Downs and Steve Holmes, the original Buster Brown founder, was not something anyone really planned.

"I don't know," he said. "I didn't really think I would gig around after the last go-around I had with Island Records."

Friend Wayne Holsclaw, who has also gigged around Louisville a few times over the years, used to watch Buster Brown as a fan. After he and his wife befriended the Edwards family after its return to Louisville, he wasn't terribly surprised that Edwards found his way back to where he began.

"He's really a good poet and he's really a fine musician," Holsclaw said. "That's what kind of blows me away. Everyone likes to say Louisville is a small Austin (Texas). There has been some talent that has floated through this town over the years, but you don't go as far as he's gone without having a lot of talent to back it up. There's not too many people in Louisville who've done what he's done."

It's almost eerie that Edwards' name barely even shows up in music annals. Go to Foreigner's Web site and you won't even find his name. The band's biography says, "(Gramm) and Jones began arguing and, in 1989, Gramm left the group to form another band called Shadow King. Foreigner, in turn, replaced Gramm with an unknown singer and carried on. Neither band, however, saw much commercial success and both groups broke up in 1991."

That's it. On Allmusic.com, a generally reliable Web resource, the story goes like this: "Gramm left the band in the late '80s for a solo career. Foreigner recruited a new lead singer but Gramm's writing and distinctive vocals are sorely missed."

Poof. As if it never happened. Edwards smiles at this too, obviously feeling no pain from this lack of recognition.

Back Home in Louisville

Years later, Buster Brown made an unexpected recent return as part of the SunCom Rockin' at Riverpoints series, opening for the Romantics.

The crowd buzzed prior to the show, questioning whether this was actually a Buster Brown gig. Was it a joke? A rumor? As it turns out, it was none of these, and the show turned out to be a successful homecoming.

Holmes, after all these years, was quite happy with the response Buster Brown got.

"I feel real good about it," he said. "It's fun. And it feels like riding a bike again."

Holmes plays full time these days with Tanita Gaines' band and had a full time gig with Dallas Moore for several years before medical problems forced him to get out. But he said the new Buster Brown, which is now a trio with Kevin Downs playing bass, is working on original music and is looking forward to several gigs in the near future.

The band will play August 11 in Bardstown, Ky., at Lynn's Bar and Grille on Hwy. 49 and will also play at Annie's in Cincinnati on August 31. There's also a tentative slot sharing a bill with Blonde Johnson at Coyote's here in Louisville this month. He said the band may even record a CD to sell locally.

"We all have kids and stuff, so I doubt anything serious will come of it," Holmes said. "But for now were having a lot of fun and playing nice jobs and just taking it a month at a time."

All this sounds like a great time, at least to Edwards: "I was missing out on the fun I'd had. With the record companies and depending on it for an income, I was eager to get away from the whole thing. I did that for seven or eight years. Then when I came back to Louisville, it seemed like a place where I could have fun and not deal with all the garbage.

"I used to pick up the guitar now and then, and I'd say, 'Man ...'" So when the opportunity came around to do a show now and then as Buster Brown again, the choice wasn't difficult to make.

"We were counting it up the other day," he said, "and it was 25 years ago that we played our first gig together as Buster Brown."

A smile and another shake of the head followed. A few moments later, Edwards draped his backpack across his back, thanked the writer who'd spent more than an hour with him in the tiny Highlands coffee shop and headed off toward home. One would assume it was like old times, long before Los Angeles, recording contracts, King Kobra or Mick Jones came into his life.

He seemed more than happy to be reliving those times.

This story was originally published in the magazine Louisville Music News, August 2001 edition.